Interview with Thierry Coquelet

| |

| Author |

|

|---|---|

| Genre | Interview |

| Published | EF Issue 2015.2 |

| Pages | 12-17 |

| Website |

|

An interview with Thierry Coquelet found on pages 12-17 of the digitally released Spring 2015 EF.

Article Transcript

Tasiir and Amy:It was a gift to meet Thierry Coquelet and an honor to have the opportunity to talk to him for the members of ISCA. In life, when you encounter a soul like Thierry, you know you are in the presence of someone very special. He is a gentle, kind and thoughtful human being, and this translates through his expression as an artist. He was recently a guest speaker at Eurocature 2014 in Vienna, Austria. It is here where he took time to share his thoughts on his artistic philosophy and techniques. Thierry Coquelet is from Angers, France, and works in the architecture field. He is also an accomplished artist and caricaturist. Thirty of his caricatures were recently published in the book “Wanted!” which features caricature drawings of cowboys and Indians by seven pivotal caricature artists of our modern time. In addition, he is currently working on a book with Jean-Marc Borot and (Jim) Maëster that will be published in the near future.

Q: When do you first remember being interested in art?

A: My first interest in art was when I was 6 or 7, watching my father draw and paint. I loved to watch him create figurative landscape paintings as an amateur artist, and as a child his work was very realistic to me. I tried to reproduce what I saw him create. My dad is a part of me, and my artwork. I actually began drawing before I could write.

Q: You often use a ballpoint pen for your caricatures. This is not a very forgiving tool. Why do you choose to use the ballpoint pen?

A: I use a ballpoint pen with my architecture renderings, so it is a tool I always have around me. It was just a natural transition for me to use it with my caricatures in my art. I have been drawing with a ballpoint pen since the 1970s. Although people said it was not popular to draw with it —it was obvious to me —a Pilot Fine for renderings and sometimes a Bic Cristal for sketches. The Pilot Fine allows me to draw very thin and straight lines, while the Bic, with its bigger ball, is a softer and more flexible tool. I use one or the other, depending on both the kind of drawing and paper being used. Some people, when they look at my work containing a lot of blackness, think it is some sort of print work, but it is created with a pen. The ballpoint pen is a tool with many constraints. The main disadvantage of a ballpoint pen is that you can’t erase like with a pencil and if I make a mistake, I have to start the drawing again. Another disadvantage is when you begin a line, it can make an ink droplet. I will sometimes use a paintbrush with white acrylic to hide the ink droplets. The drawings I do with the pen are very small. Most of them can easily fit on an A5 format. The time I spend on even the smallest drawings is a very long time. I use a lot of crosshatching. The first thing that comes to mind when I think of crosshatching is the work of Gustave Doré, the famous French painter and engraver of the 19th century. What I learn from looking at his work is that crosshatching is a way to develop volume, not just shades of gray.

Q: You have a very unique and beautiful way of looking at the creation of a piece of art. Talk to us a little bit about how you come up with the concept for your pieces.

A: I have a certain freedom, being a nonprofessional, to draw the things I want to draw, not politicians or pop culture, but what I want to draw. The act of NOT drawing these characters is just as important to me as drawing the things that ARE important to me. When I look at reference photos, I look for both the likeness and for the soul of the person in the photos. When I first work on a piece, I do not go for the likeness. I work on the likeness afterwards. Finding a likeness is part of the research process. It is the emotional part of the photo that is the main focus for me. Likeness is based on emotions, not the opposite. This is not a choice that I made consciously, but rather I just noticed that it happened to develop this way, for me. Many caricature artists work differently. Some begin with the physical likeness and they find the soul of their subject during this exploration. In the same way, some musicians start a song by writing the music before the lyrics, while others create the opposite way. I have spoken with other caricature artists and we have come to the conclusion that 80 percent of the drawing is the technical work —like the structure, the shapes, the texture of the skin, the hair, etc… But, there is 20 percent of the drawing that is invisible, that we only feel. This 20 percent is that which captures the personality of the person, what the person is like on the inside… the soul of the person, their truth. It is this 20 percent that validates the technical work on the 80 percent. There is still a balance between technique and emotion. Sometimes the way I exaggerate or render the piece can make the SOUL likeness better. For example, if I had chosen to use watercolor to paint Marlene Dietrich based on the same shapes, I do not think I would have arrived so closely to a soul likeness, in the end. (I’m not a good watercolorist!) The subject is important, but so is the execution.

Q: Tell us about your execution process…

A: When I used to do portraits, I felt the look of the eyes was very important. I used what I knew about portraits and applied it to caricature. I found it worked. I found caricature can express as many things as portrait. I also used what I knew about architecture to caricature. It can take me between 2 days and 1 week to complete a work. Some caricatures come easy, and others are hard to pen. So, in my first sketches, I try to catch the emotion inspired by the reference picture I chose. Thus I try to connect to the person I am drawing. Of course, I also try to find a way to the physical likeness, but this is not the main goal at that time. These first sketches look much more like dirty doodles than what we can expect from real sketches. When a sketch becomes interesting to me, I scan it in order to start fixing the shapes on the screen, always according to my feelings about this person. The digital process allows me to cut, move, stretch, reduce or expand all the parts of the face very quickly and easily. Then I print the result, put the print on the light table, draw another sketch from this one, scan it again, etc., until I’m quite satisfied with the result. At the end, I do a final rendering. As you can see, this is a much more sensitive than intellectual exercise. In a way, it looks like modeling on a sort of architecture, a structure that must become stronger and more efficient, step by step. I have a technique that I have developed that works for me, my life and my day job. I work a little in the morning, a little in the afternoon and then a little in the evening. These breaks allow me to come back and see things with fresh eyes. I both benefit from and allow for time between stages of creating my drawings.

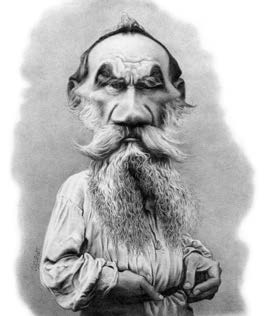

Q: Some of your reference photos are very old and grainy, like your reference for your Tolstoy drawing. How do see things within a grainy photo?

A: Sometimes you can’t see things, so you look at yourself and ask, “What does this wrinkle look like on me?” and then re-create it. With Tolstoy, I had to IMAGINE his beard. I also wanted to create whimsical movement in the drawing. I could not reproduce the beard because the photo was blurred, due to its bad resolution. So, on another piece of paper, I doodled what I thought his beard would look like, and used a lot of movement. Then when I found something I liked, I added it to the drawing. When you are working from a bad photo, you have to use the imagination. When I use my imagination, it is MY opinion being added to the piece. I normally try not to do this. When I draw, normally, I try to put the opinion of the character I am drawing into the piece, so I like to try to stick to the photo a bit more. A drawing is a lot like a documentary of the character’s life. When we exaggerate, we are already using a great deal of our imagination, our “opinion,” in the piece. So, I do not try to put myself in the drawing too much more beyond the exaggeration, but rather make it like a documentary of the person I am drawing. There is a spirited game between me and the characters I am drawing. The drawing will actually speak to me as it’s being created and tell me how to render it. Sometimes, I want to draw fast and use fewer lines so a piece will go quicker. But, then the character of the piece will demand more lines as I am creating, and I prefer drawing from a photograph than from the real life except for landscapes— it’s easier. In a way, I guess it would not work if I call Woody Allen or Michelle Pfeiffer to tell them, “Hello, would you come at home today because I’d like to draw a caricature of you?” On a photo, you have the light and the lines all in front of you, and all the time you need. If I can’t get a drawing to work exactly off the photo, I will draw without the photo and use my imagination, using what I remember from the drawing. I then will look at the photo again and tighten the drawing. One of the things I like about old photography is many times there is a special light on the subject and darkness in the background. Pieces with darkness or lots of shadow in the background take forever. Sometimes I draw a character from the 19th century and I choose not to represent the dark background — just a halo around the head and the shoulders— and it seems like something is missing. Sometimes the background is very important because it gives the character its depth.

Q: What are some caricatures where you are satisfied with your outcome?

A: Well, I am not really satisfied with any of them, always considering that each drawing is the sketch for the next one. But, the pieces that do work for me are usually the ones that I took great pleasure in creating. For example, I took pleasure in creating both Marlene Dietrich and Virginia Woolf. Sometimes I feel like the character of the piece will speak to me and tell me what to do. For example, Virginia Woolf would talk with me and say, “Let’s go… let’s try this … let’s keep going.” With Woolf, I asked myself three questions before doing her caricature: (1) Can I draw someone so tortured and tragic? (2) Is it decent to draw someone so tortured and tragic? (3) How do I do this? I spent a long time with the drawing of her, and with her in spirit as I drew her. I found her company to be quite pleasant. My friend Jean Mulatier says he stays humble when he draws because when one reproduces a person’s soul, it is not yours, it is theirs, and you have to ask the subject what is the good way to present them.

Q: What makes a caricature successful to you?

A: LIKENESS.

Q: Who are some caricature artists whom you admire?

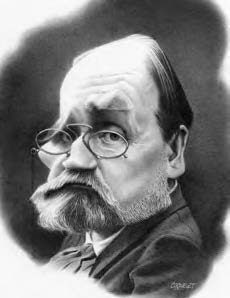

A: Two people I admire tremendously, from when I was young, are Jean Mulatier and Jim Maëster. I consider them to be masters. I discovered Mulatier on Saturdays watching a TV show called “Tac au tac” doing a caricature of Leonid Brezhnev. The way he drew faces seemed to be in perfect harmony with each other. What inspired me long-term with Mulatier was how he sculpted the faces. It is perfect the way he establishes the balance between the plains and the crevices in the face. What also is very impressive is the balance in the humanness in his drawings and the respect he has toward his subject. He has wonderful accuracy in his portrayal and the likeness. His work in the 1970s was really revolutionary in the world of caricature. It had the precision of a photograph at that time. His works were published worldwide. Mulatier drew his Jimmy Carter Time Magazine cover with a “000” brush. In other words, this is a brush with maybe 1 hair. It took him a week to do the teeth. Over time, he simplified his work by applying the crosshatching technique. He has evolved his crosshatching in a personal way where it is almost like a personal calligraphy. In describing his work, he said he does not distort, but he alters the proportions. Something he taught me was NOT to be aggressive, but to focus on the likeness. Sometimes the enthusiasm we have toward caricature can turn us toward cynicism. Mulatier says one must NOT exaggerate exaggerations. Accentuation of a certain trait on the face, a reaction of cause and effect, is just the tip of the iceberg (for example, making a big nose big). It is evident and easy to decode this in his work and much more difficult to put it into practice! He is a great teacher. Even as a child —everything seemed clear to me in his works. Many people compare my work to his work, which I consider a great honor, but he is a mountain and I am a pebble. The other person who influenced me intensely is Jim Maëster. Maëster always introduces the second soul into his drawings. For example, it is easy to get lost in the look of his wonderful caricature of Marilyn Monroe. Maëster is very popular in comics in France. What I liked about his comics is they are very dense with a lot of movement in them. His work is full of humor and contains lots of caricatures of famous people and parodies with film and TV. You have to read his works more than once to find all the details he has hidden in his comics. The spirit of his work invokes the spirit of Mad Magazine. Maëster himself talks a lot about the admiration he has for people like Mort Drucker. Always the comic book artist — he also exaggerates the background, the accessories and the body. Many times with caricature the focus is only a drawing of the face, but Maëster includes the body, background and accessories —what the French call the secondary traits. He does not forget to exaggerate the ears, for example, and the clothing folds. I mention this because I forget to exaggerate the ears sometimes. He is also wonderful at exaggerating the hands. This is something else I admire —the hands are considered difficult to draw. One of the things he masters well is he makes it all about the whole piece, and it all fits together. It’s not just a face. He also is the best in caricaturing female faces in comics, from my own point of view. Both Mulatier and Maëster’s approach are very different, but both portray something positive in their subject, where their work transcends caricature and allows them to portray the depth of their subject. Moreover, those of us who have the joy to know them know that they are wonderful people. Their influence on my work is tremendous.

Q: What are your thoughts on digital caricature vs. traditional caricature?

A: Sometimes I do digital caricature, ALWAYS beginning with a traditional sketch. I prefer traditional to digital, because caressing the paper with a traditional tool is much more sensual than touching plastic to plastic. Having said that, I recognize that the digital work allows me to do something in a day that would take me five days using my traditional method. There is a legitimate question that I ask myself from an economic point of view — whether it makes sense to spend so much time on a piece that is consumed so quickly in our digital world. From an economic point of view, it is not viable. I do not know an editor in France today who would pay a traditional artist the amount that would be due to them for doing a piece that a digital artist could do in much less time.

Q: In your eyes, where do you see the future of caricature?

A: Well, in France, caricature is not what the editors prefer to publish. All the covers of American magazines that Jason Seiler painted these last years, for example, do not exist in France. Here, these kinds of magazines would use photos instead of caricatures. Maybe caricature is considered much more like a joke than an art, even though France is also known for its very long history of caricature. A few newspapers publish caricatures either on their front page (“Le Monde”) or they are fully dedicated to caricature (“Charlie Hebdo” and “Le Canard enchaîné”, etc.), but this sort of caricature is generally based on biting and corrosive humor about politicians, religions and society. It is a kind of social journalism much more than an artistic consideration. Many of us are trying to work our caricatures using likeness and not wickedness. We are attempting to make caricatures with a lot of balance as a tribute to represent the character. There is not ugliness … exaggerating for exaggeration’s sake. In France, there is no equivalent to ISCA, Eurocature or Asociación Española de Caricaturistas; but, some very good friends of mine are actually working on this, because we are aware of the importance of caricature as an artistic and cultural media, including in the matter of the protection of the author’s rights. So, I really hope that the future of caricature will be better in my country. As you can see, the future of caricature is not a debate between digital and traditional artists, but rather that the existence of caricature as an art form is at stake. Some caricature artists like Jean-Marc Borot and Charles Da Costa, for example, have their work published in books. These are good samples of a new breath in caricature happening in publishing. Maëster himself became a publisher in order to promote caricature as a true art form. “Wanted!” is a real art book much more than a single illustrated book about Western movies. As a nonprofessional, I just try to contribute to this promotion.

Q: What advice would you like to give to artists who want to learn caricature?

A: Draw, draw, draw! The best way to learn is to draw often, and not just caricature, but drawing in general. First, draw shapes, lights, shadows, lines, faces, landscapes… all things. Second, it’s important to see what the artists over time have drawn. Learn from history. A great artist for this is Watteau —an artist in the 18th century. He is a master in sketching.

Q: Thank you for your time with us today. Are there any last thoughts you would like to share with us?

A: In caricature, and in art, happiness is not the goal but the path. Thank you very much.

See Also

External Links

This Navigation box may not show up on mobile browsers. Please see Exaggerated Features Issue 2015.2 for the full contents of this issue if the navigation box does not display.